This article originally appeared on the Rethinking Childhood website and is republished with the permission of the author, Tim Gill.

This week marked a milestone in the UK street play movement, with the publication of three new reports.

The first is an evaluation report by the University of Bristol [pdf link], published by Play England, which looked mainly at the health outcomes for children. The second is a report [pdf link] from Playing Out, the Bristol-based national hub for street play, of a survey of people directly involved in street play sessions. The third, written by me [pdf link] and also published by Play England, explores the issues around taking street play initiatives forward in disadvantaged areas.

This blog post from Playing Out gives a helpful overview of the three reports (as well as a flavour of the high level of press interest).

This blog post from Playing Out gives a helpful overview of the three reports (as well as a flavour of the high level of press interest).

All three reports focus on the model of regular, resident-led, temporary road closures in residential streets. Taken together, they show that street play can have a profound and lasting impact on both children and the wider community. The model is also low-cost, sustainable and widely applicable (though there are challenges in hihgly disadvantaged areas and/or housing estates with non-traditional road layouts).

Hence it is hard to argue with the statement from Playing Out that the model is “any policy-maker’s dream come true” and that there is an urgent need for both national and local government to “provide the policy and practical support needed to make it easy for residents anywhere to initiate and sustain it.”

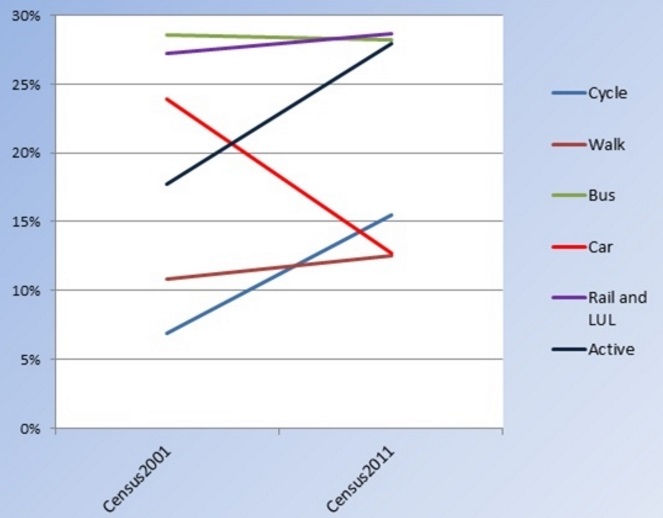

Hackney travel changes 2001-2011It is telling that one of the areas where the model has been most successful – the London Borough of Hackney, where the current total is round about 50 streets – is also an area that has become dramatically less car-dominated in recent years. Statistics from the 2001 and 2011 censuses show:

Hackney travel changes 2001-2011It is telling that one of the areas where the model has been most successful – the London Borough of Hackney, where the current total is round about 50 streets – is also an area that has become dramatically less car-dominated in recent years. Statistics from the 2001 and 2011 censuses show:

- The proportion of trips made by car halved

- The number of walking commuters doubled

- The proportion of people with access to a car fell by over 20%

- More residents cycle to work than any London borough, while more residents cycle (15.4%) than drive (12.8%).

In truth, these changes are happening all over London [pdf link], though at a slower rate than in Hackney. Across my home city – and in many other cities around the world, including Calgary, Lyon and Melbourne [scroll down] – cars are vanishing from neighbourhoods.

This poses the question: what might residential streets become, once they are no longer the sole preserve of the car? What Hackney shows is that many could become places for play and community life.

There is little doubt that the dominance of the car is the biggest barrier to making cities more sustainable and liveable. But equally, many urban residents need access to cars, and are hostile to changes that may make their lives more difficult. Tackling car dependence is perhaps the definitive wicked issue for urban policy makers.

This is where play streets come in. They show ordinary people how their lives would be improved if their neighbourhoods were less car-dominated, building support for policies that make cities more sustainable and liveable for everyone. They help people join the dots between big, complex topics like pollution, transport planning and community cohesion on the one hand, and everyday life in residential streets on the other. And they help to create virtuous circles that build sustainable lifestyles and attitudes across the generations and over the decades to come.

This is not just speculation: revealing personal accounts from street play advocates show the process in action. To take a few quotes from the Playing Out survey:

- “I feel more empowered to make positive change in my community and feel l can positively impact the street where I live. I feel a greater sense of ownership of my street. I feel more confident at giving my daughter independence.”

- “I feel inspired that there are things that can be done to help not just kids play outside but everyone to experience the city without fear of traffic.”

Let’s be clear: play streets are not a silver bullet for making cities more child-friendly. Much more is needed: more investment in walking, cycling and public transport, smarter ways to tame traffic in residential streets, more attractive, better-managed parks and green spaces (and better access to them), and better-designed housing estates and new towns. (My Churchill Fellowship will explore how different cities have pursued these goals.)

That said, I still believe that resident-led street play is the most promising child-friendly idea to have emerged in the last 20 years. The reports published on Monday prove the difference play streets make to children, families and communities. They also show the power of a vision of less car-dominated, more child-friendly neighbourhoods.

References

Playing Out survey report, July 2017

Street play initiatives in disadvantaged areas: experiences and emerging issues (published by Play England 2017)

New evidence shows impact of street play (Playing Out, July 2017)

First ever area-wide evaluation of street play proves its potential (Rethinking Childhood, March2015)

How Hackney became London’s most liveable borough (Design Council website, June 2014)

Roads Task Force - Technical Note 2: What are the main trends and patterns for road traffic in London? (Transport for London, 2012)

How street play can help save cities from the car (Rethinking Childhood, January 2017)

Announcing a new project to build the case for more child-friendly cities (Rethinking Childhood, March 2017)